F=ma 2024 solutions

P01

An archer fires an arrow from the ground so that it passes through two hoops, which are both a height h above the ground. The arrow passes through the first hoop one second after the arrow is launched, and through the second hoop another second later.What is the value of h?

(A) 5 m

(B) 10 m

(C) 12 m

(D) 15 m

(E) There is not enough information to decide.

P01 solution

Recall that the total time of flight for a projectile is given by:

\[ T = \frac{2v_{0y}}{g}\]

Since the two hoops are at the same height h , it takes the same time t0 for the arrow to travel from the second hoop to the ground as it takes for the arrow to travel from the ground to the first hoop. Thus, we have:

\[ T = 3t_0\]

So the particle has initial vertical velocity

\[ v_{0y} = \frac{3g t_0}{2}\]

Using a kinematics equation ,

\[ h = v_{0y}t_0 - \frac{1}{2}g t_0^2 = g t_0^2\]

Finally:

\[ h = g t_0^2 = 10t_0^2 = 10(1)^2 = 10 \, \text{m}\]

Thus the answer is:

\[ \text{B. } 10 \, \text{m}\]

P02

An amusement park ride consists of a circular, horizontal room. A rider leans against its frictionless outer walls, which are angled back at 30° with respect to the vertical, so that the rider’s center of mass is 5.0 m from the center of the room. When the room begins to spin about its center, at what angular velocity will the rider’s feet first lift off the floor?

(A) 1.9 rad/s

(B) 2.3 rad/s

(C) 3.5 rad/s

(D) 4.0 rad/s

(E) 5.6 rad/s

P02 solution

We go to the rotating frame and add the (fictitious) centrifugal force \(m\omega^2 r\) directed outward. When the rider’s feet lift off the floor, we only have the rider’s weight and the normal force from the wall. Balancing forces,

\[ N \cos \theta = m\omega^2 r\]

\[ N \sin \theta = mg\]

Dividing the equations,

\[ \cot \theta = \frac{\omega^2 r}{g}\]

\[ \omega = \sqrt{\frac{g \cot \theta}{r}} = \sqrt{\frac{(10 \text{ m/s}^2) \cot(\pi/6)}{5 \text{ m}}} = 1.9 \text{ rad/s}^{-1}\]

so the answer is

\[ \text{A. } 1.9 \, \text{rad/s}\]

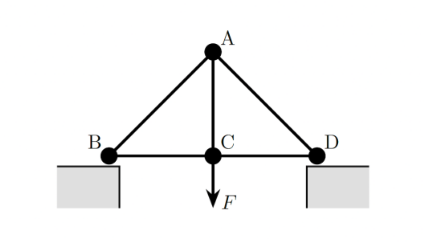

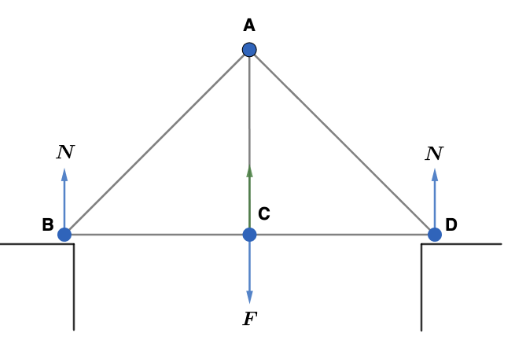

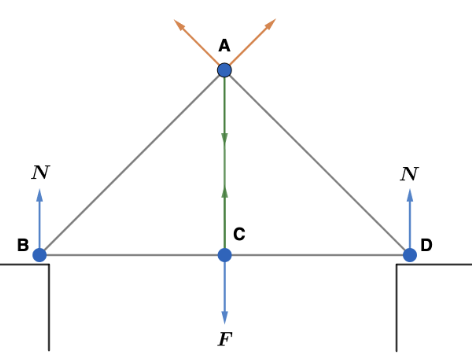

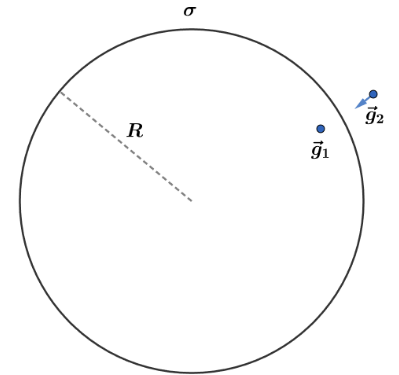

P03

A simple bridge is composed of five thin rods rigidly connected at four vertices.The ground is frictionless, so it can only exert vertical normal forces at points \(\text{B }\) and \(\text{𝐷. }\) The weight of the bridge is negligible, but a person stands at its middle, exerting a downward force \(\text{F }\) at vertex \(\text{C. }\) In static equilibrium, each rod may experience either tension or compression. Which of the following statements is true?

(A) Only the vertical rod is in tension.

(B) Only the horizontal rods are in tension.

(C) Both the vertical rod and the diagonal rods are in tension.

(D) Both the vertical rod and the horizontal rods are in tension.

(E) All of the rods are in tension.

P03 solution

Balancing forces in the vertical direction at point \(\text{C }\), we see that rod \(\text{AC }\) must be in tension (the force of the vertex on the rod would be downward by Newton’s 3rd law).

Then, balancing forces in the vertical direction at point \(\text{A }\), we see that rods \(\text{AB }\) and \(\text{AD }\) must be in compression.

so the answer is \(\text{A. }\)

P04

A bouncy ball is thrown vertically upward from the ground. Air resistance is negligible, and the ball’s collisions with the ground are perfectly elastic. Which of the following graphs shows the kinetic energy of the ball as a function of time? Assume the collisions are too quick for their duration to be seen in the plot.

P04 solution

From the initial launch to the first bounce, we have

\[ v(t) = v_0 - gt\]

so the kinetic energy is

\[ K(t) = \frac{1}{2} m v(t)^2 = \frac{1}{2} m (gt - v_0)^2\]

which is an upward-opening parabola. Since collisions are elastic, \(\text{K(t)}\) is periodic after every bounce,

so the answer is \(\text{D }\)

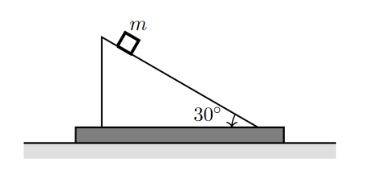

P05

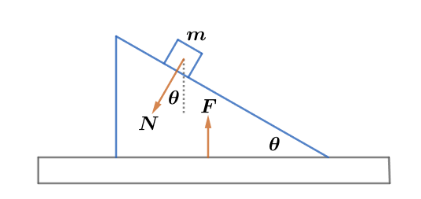

A massless inclined plane with an angle of \(30^\circ\) to the horizontal is fixed to a scale. A block of mass \(text{m}\)is released from the top of the plane, which is frictionless.As the block slides down the plane, what is the reading on the scale?

(A) \(\frac{\sqrt{3}mg}{4}\)

(B) \(\frac{mg}{2}\)

(C) \(\frac{3mg}{4}\)

(D) \(\frac{\sqrt{3}mg}{2}\)

(E) \(\text{mg }\)

P05 solution

Choosing the inclined plane as our system and balancing forces in the vertical direction,

\[ F = N \cos \theta\]

Recall the normal force on a block sliding down an inclined plane is \(N = mg \cos \theta\), so

\[ F = mg \cos^2 \theta = mg \cos^2 (\pi/6) = \frac{3mg}{4}\]

so the answer is \(\text{C }\)

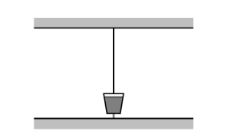

P06

A pendulum is made with a string and a bucket full of water. When the string is vertical, the bottom of the bucket is near the ground.

Then, the pendulum is set swinging with a small amplitude, and a very small hole is opened at the bottom of the bucket, which leaks water at a constant rate. After a few full swings, which of the following best shows the amount of water that has landed on the ground as a function of position?

P06 solution

The amount of water \(\Delta V(x)\) (in an interval \(\Delta x\)) at position \(x\) is proportional to the amount of time \(\Delta t(x)\) the bucket is there. Since \(v = \frac{dx}{dt}\), we estimate

\[ \Delta t(x) = \frac{\Delta x}{v(x)} \propto \frac{1}{v(x)}\]

To find \(v(x)\), we conserve energy for simple harmonic motion,

\[ \frac{1}{2} k A^2 = \frac{1}{2} k x^2 + \frac{1}{2} m v^2\]

\[ v^2 \propto A^2 - x^2\]

\[ v \propto \sqrt{A^2 - x^2}\]

Thus,

\[ \Delta V(x) \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{A^2 - x^2}}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

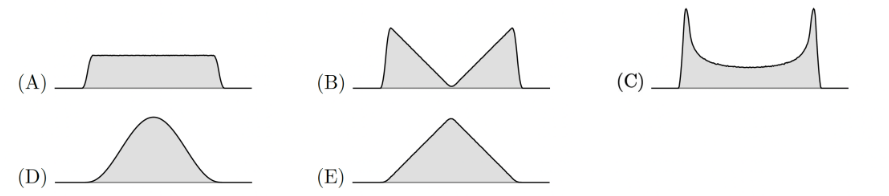

P07

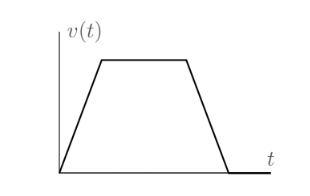

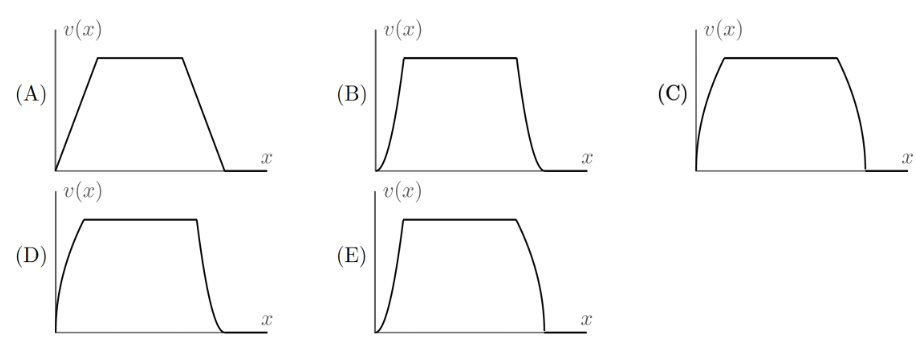

A particle travels in a straight line. Its velocity as a function of time is shown below.

Which of the following graphs shows the velocity as a function of distance \(v(x)\) from its initial position?

P07 solution

In Part I of the motion, we have constant acceleration \(a\), so using a kinematics equation,

\[ v^2 = 0^2 + 2ax\]

\[ v(x) = \sqrt{2ax}\]

In Part II of the motion, we have constant velocity, so

\[ v(x) = v_0\]

In Part III of the motion, we have constant acceleration \(-a\), so using a kinematics equation,

\[ v^2 = v_0^2 + 2(-a)x\]

\[ v(x) = \sqrt{v_0^2 - 2ax}\]

Combining the three parts, the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

P08

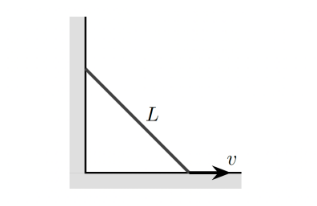

A rod of length \(L\) is sliding down a frictionless wall.

When the rod makes an angle of \(45^\circ\) to the horizontal, the bottom of the rod has speed \(v\). At this moment, what is the speed of the middle of the rod?

(A) \(\frac{v}{2}\)

(B) \(\frac{v}{\sqrt{2}}\)

(C) \(v\)

(D) \(\sqrt{2} v\)

(E) \(2v\)

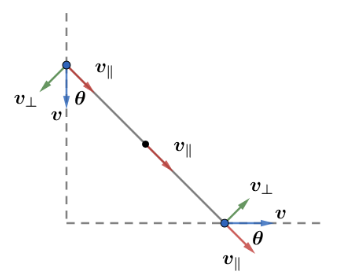

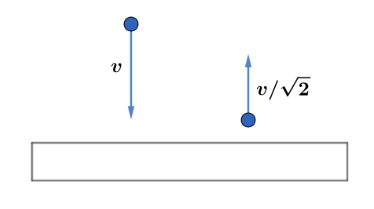

P08 solution

The top of the rod is moving downward because it is sliding along the wall. The speed of the top is also \(v\) since the component of velocity \(v_{\parallel}\) parallel to the rod must be the same at both ends. We have

\[ v_{\parallel} = v \cos \theta\]

The component of velocity \(v_{\perp}\) perpendicular to the rod has the same magnitude but opposite directions at the two ends, which means the instantaneous axis of rotation is at the middle of the rod. Thus,

\[ v_{\text{mid}} = v_{\parallel} = v \cos(\pi/4) = \frac{v}{\sqrt{2}}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

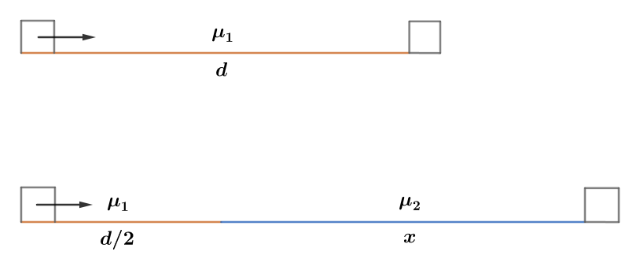

P09

When a car’s brakes are fully engaged, it takes \(100 \, m\) to stop on a dry road, which has a coefficient of kinetic friction \(\mu_k = 0.8\) with the tires. Now suppose only the first \(50 \, m\) of the road is dry, and the rest is covered with ice, with \(\mu_k = 0.2\). What total distance does the car need to stop?

(A) \(150 \, m\)

(B) \(200 \, m\)

(C) \(250 \, m\)

(D) \(400 \, m\)

(E) \(850 \, m\)

P09 solution

The energy dissipated by friction on the first track is

\[ E_d = f_1 d = \mu_1 mgd\]

The energy dissipated by friction on the second track is

\[ E_d = f_1 \left(\frac{d}{2}\right) + f_2 x = \frac{\mu_1 mgd}{2} + \mu_2 mgx\]

Since these are the same,

\[ \mu_1 mgd = \frac{\mu_1 mgd}{2} + \mu_2 mgx\]

\[ \frac{\mu_1 d}{2} = \mu_2 x\]

\[ x = \frac{\mu_1 d}{2\mu_2}\]

The total distance on the second track is

\[ D = \frac{d}{2} + x = \frac{d}{2} \left( 1 + \frac{\mu_1}{\mu_2} \right) = \frac{100 \text{ m}}{2} \left( 1 + \frac{0.8}{0.2} \right) = 250 \text{ m}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

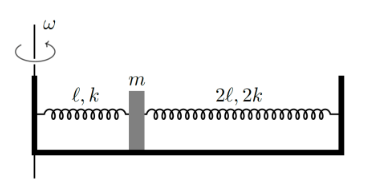

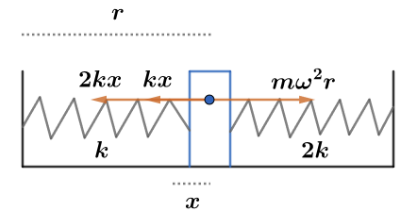

P10

A block of mass \(m\) is connected to the walls of a frictionless box by two massless springs with relaxed lengths \(\ell\) and \(2\ell\), and spring constants \(k\) and \(2k\) respectively. The length of the box is \(3\ell\). The system rotates with a constant angular velocity \(\omega\) about one of its walls.

Suppose the block stays at a constant distance \(r\) from the axis of rotation, without touching either of the walls. What is the value of \(r\)?

(A) \(\frac{2k\ell}{2k - m\omega^2}\)

(B) \(\frac{2k\ell}{2k + m\omega^2}\)

(C) \(\frac{2k\ell}{3k - m\omega^2}\)

(D) \(\frac{3k\ell}{3k - m\omega^2}\)

(E) \(\frac{3k\ell}{3k + m\omega^2}\)

P10 solution

We go to the rotating frame and add the (fictitious) centrifugal force \(m\omega^2 r\) directed outward. Since the block is at rest, we balance forces

\[ kx + 2kx = m\omega^2 r\]

where \(x\) is the displacement of the block. Since the block starts at distance \(l\) from the axis, we have

\[ x = r - l\]

Solving for \(r\),

\[ 3k(r - l) = m\omega^2 r\]

\[ (3k - m\omega^2) r = 3kl\]

\[ r = \frac{3kl}{3k - m\omega^2}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

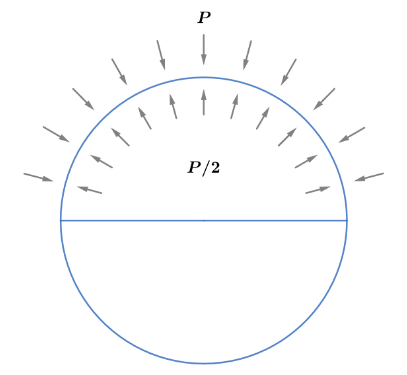

P11

Two hemispherical shells can be pressed together to form an airtight sphere of radius \(40 \, \text{cm}\). Suppose the shells are pressed together at a high altitude, where the air pressure is half its value at sea level. The sphere is then returned to sea level, where the air pressure is \(10^5 \, \text{Pa}\). What force \(F\), applied directly outward to each hemisphere, is required to pull them apart?

(A) \(25,000 \, \text{N}\)

(B) \(50,000 \, \text{N}\)

(C) \(100,000 \, \text{N}\)

(D) \(200,000 \, \text{N}\)

(E) \(400,000 \, \text{N}\)

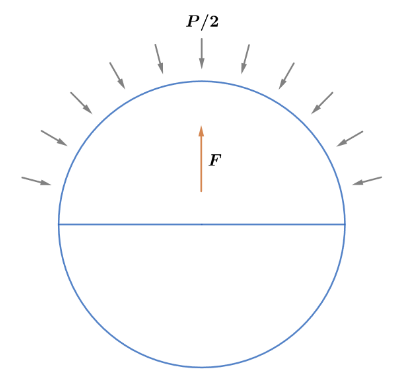

P11 solution

When the sphere is returned to sea level, the air pressure outside is \(P\) while the air pressure inside is \(P/2\). At any point on the sphere, the force on the outside is double the force on the inside, so it is equivalent to consider air outside to be at pressure \(P/2\) and vacuum inside the sphere.

P12

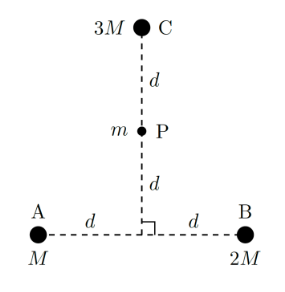

A space probe with mass \(m\) at point \(P\) traverses through a cluster of three asteroids, at points \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\). The masses and locations of the asteroids are shown below.

What is the torque on the probe about point \(C\)?

(A) \(\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \frac{GMm}{d}\)

(B) \(\frac{1}{2} \frac{GMm}{d}\)

(C) \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \frac{GMm}{d}\)

(D) \(\frac{GMm}{d}\)

(E) \(\frac{\sqrt{2} GMm}{d}\)

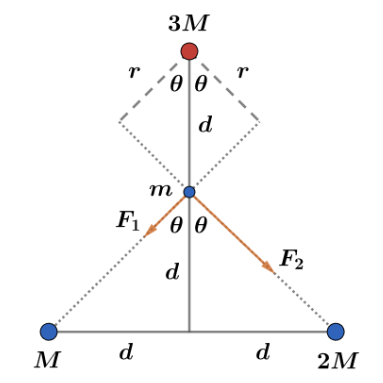

P12 solution

Since the location of the \(3M\) asteroid is chosen as the pivot point, its gravitational force on the space probe doesn’t contribute to the torque. The net torque is then

\[ \tau = \tau_2 - \tau_1 = (F_2 - F_1) r = \left[ \frac{G(2M)m}{(d\sqrt{2})^2} - \frac{GMm}{(d\sqrt{2})^2} \right] (d \cos\theta) = \frac{GMm}{(d\sqrt{2})^2} d \cos(\pi/4)\]

\[ = \frac{GMm}{2d^2} \frac{d}{\sqrt{2}} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \frac{GMm}{d}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{A}\).

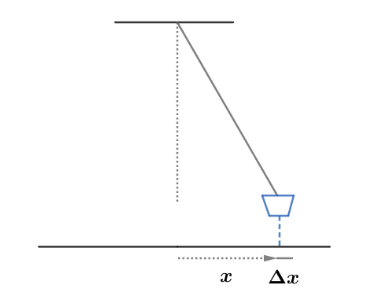

P13

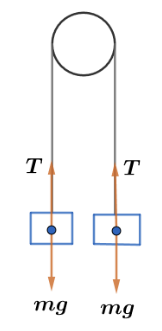

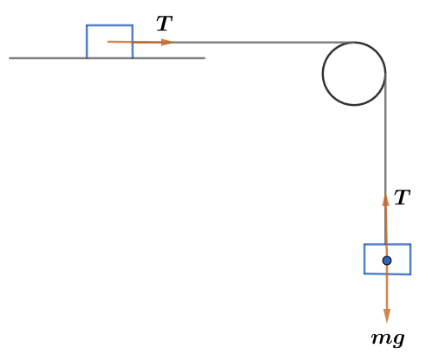

Two frictionless blocks of mass \(m\) are connected by a massless string which passes through a fixed massless pulley, which is at a height \(h\) above the ground. Suppose the blocks are initially held with horizontal separation \(x\), and the length of the string is chosen so that the right block hangs in the air as shown.

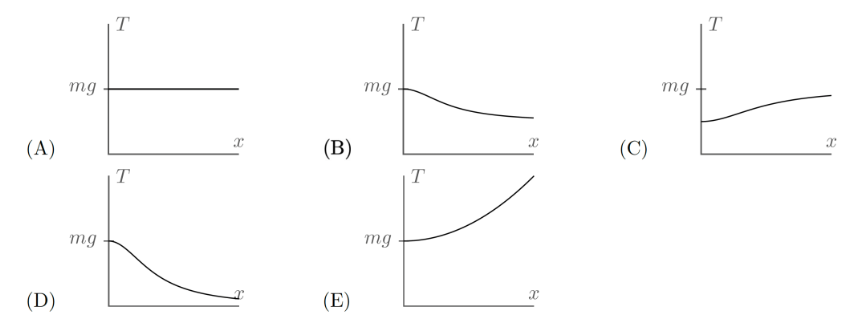

If the blocks are released, the tension in the string immediately afterward will be \(T\). Which of the following shows a plot of \(T\) versus \(x\)?

P13 solution

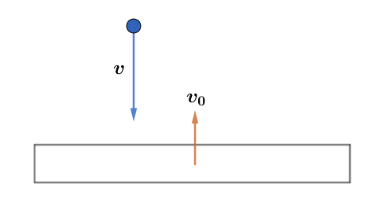

In the limiting case \(x \to 0\), the setup reduces to a standard Atwood machine with two equal masses, so

\[ T(x \to 0) = mg\]

In the limiting case \(x \to \infty\), the setup reduces to the system shown below:

P14

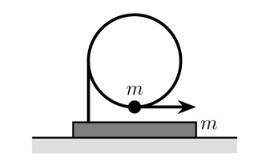

- A bead of mass \(m\) can slide frictionlessly on a vertical circular wire hoop of radius \(20 \text{ cm}\).

The hoop is attached to a stand of mass \(m\), which can slide frictionlessly on the ground. Initially, the bead is at the bottom of the hoop, the stand is at rest, and the bead has velocity \(2 \text{ m/s}\) to the right. At some point, the bead will stop moving with respect to the hoop. At that moment, through what angle along the hoop has the bead traveled?

(A) \(30^\circ\)

(B) \(45^\circ\)

(C) \(60^\circ\)

(D) \(90^\circ\)

(E) \(120^\circ\)

P14 solution

Conserving linear momentum, we have

\[ mv = (m + m)v_f\]

\[ v_f = \frac{v}{2}\]

Conserving energy, we have

\[ \frac{1}{2} m v^2 = mg h + \frac{1}{2} m v_f^2 + \frac{1}{2} m v_f^2 = mg r (1 - \cos\theta) + m \left( \frac{v}{2} \right)^2\]

\[ \frac{v^2}{4} = g r (1 - \cos\theta)\]

Solving for \(\theta\),

\[ \cos\theta = 1 - \frac{v^2}{4 g r} = 1 - \frac{(2 \text{ m/s})^2}{4 (10 \text{ m/s}^2)(0.2 \text{ m})} = 0.5\]

\[ \theta = 60^\circ\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

P15

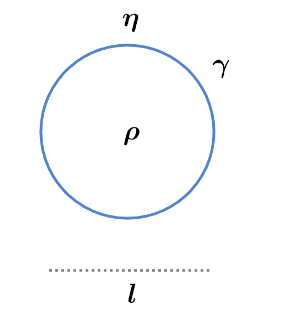

The viscous force between two plates of area \(A\), with relative speed \(v\) and separation \(d\), is

\[ F = \eta \frac{A v}{d}\]

where \(\eta\) is the viscosity. In fluid mechanics, the Ohnesorge number is a dimensionless number proportional to \(\eta\) which characterizes the importance of viscous forces, in a drop of fluid of density \(\rho\), surface tension \(\gamma\), and length scale \(\ell\). Which of the following could be the definition of the Ohnesorge number?

(A) \(\frac{\eta \ell}{\sqrt{\rho \gamma \ell}}\)

(B) \(\eta \ell \sqrt{\frac{\rho}{\gamma}}\)

(C) \(\eta \sqrt{\frac{\rho}{\gamma \ell}}\)

(D) \(\eta \sqrt{\frac{\rho \ell}{\gamma}}\)

(E) \(\frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\rho \gamma \ell}}\)

P15 solution

We can do dimensional analysis to find the Ohnesorge number \(O = O(\eta, \rho, \gamma, l)\). We are given

\[ [O] = 1\]

and

\[ F = \eta \frac{A v}{d}\]

so

\[ [\eta] = \left[ \frac{F d}{A v} \right] = \frac{(M L / T^2) L}{L^2 (L / T)} = \frac{M L^2}{T^2 L^3} = \frac{M}{L T}\]

Also recall

\[ [\rho] = \frac{M}{L^3}\]

\[ [\gamma] = \frac{[F]}{[L]} = \frac{M}{T^2}\]

\[ [l] = L\]

We are told \(O \propto \eta\) so we need to divide by \(\sqrt{\gamma}\) to cancel out dimensions of time,

\[ \left[ \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\gamma}} \right] = \frac{M}{L T} \frac{T}{\sqrt{M}} = \frac{\sqrt{M}}{L}\]

Then we can divide by \(\sqrt{\rho}\) to cancel out dimensions of mass.

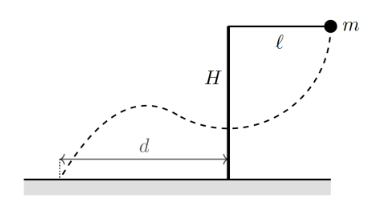

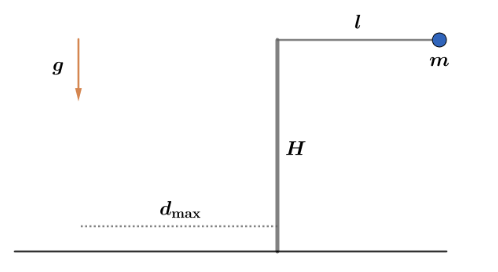

P16

A child of mass \(m\) holds onto the end of a massless rope of length \(\ell\), which is attached to a pivot a height \(H\) above the ground. The child is released from rest when the rope is straight and horizontal.

At some point, the child lets go of the rope, flies through the air, and lands on the ground a horizontal distance \(d\) from the pivot. On Earth, the maximum possible value of \(d\) is \(d_E\). If the setup is moved to the Moon, which has \(1/6\) the gravitational acceleration, what is the new maximum possible value of \(d\)?

(A) \(\frac{d_E}{6}\)

(B) \(\frac{d_E}{\sqrt{6}}\)

(C) \(d_E\)

(D) \(\sqrt{6} d_E\)

(E) \(6 d_E\)

P16 solution

We can do dimensional analysis to find \(d_{\max} = d_{\max}(\ell, H, g)\). We have

\[ [d_{\max}] = L\]

\[ [\ell] = L\]

\[ [H] = L\]

\[ [g] = \frac{L}{T^2}\]

Since \(g\) is the only input that has dimensions of time, \(d_{\max}\) must be independent of \(g\), so the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

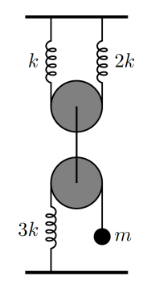

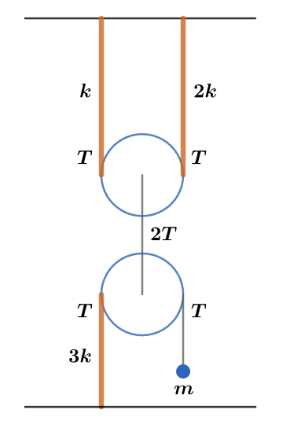

P17

Consider the following system of massless and frictionless pulleys, ropes, and springs.

Initially, a block of mass \(m\) is attached to the end of a rope, and the system is in equilibrium. Next, the block is doubled in mass, and the system is allowed to come to equilibrium again. During the transition between these equilibria, how far does the end of the rope (where the block is suspended) move?

(A) \(\frac{7}{12} \frac{mg}{k}\)

(B) \(\frac{11}{12} \frac{mg}{k}\)

(C) \(\frac{13}{12} \frac{mg}{k}\)

(D) \(\frac{7}{6} \frac{mg}{k}\)

(E) \(\frac{11}{6} \frac{mg}{k}\)

P17 solution

Let \(T\) be the tension in the bottom string (attached to the mass \(m\)). Then, by balancing forces on the pulleys, we find that the tensions in the springs are also \(T\). Looking at the mass, we have

\[ T = mg\]

After the mass is doubled,

\[ T' = 2mg\]

and the tension in the springs increases by

\[ \Delta T = T' - T = mg\]

so each spring extends by \(y_i = \frac{mg}{k_i}\). We use conservation of string to find the displacement \(y\) of the mass.

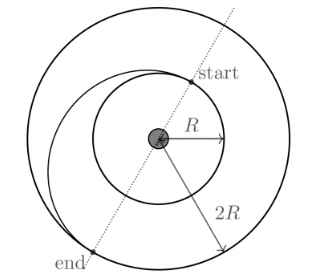

P18

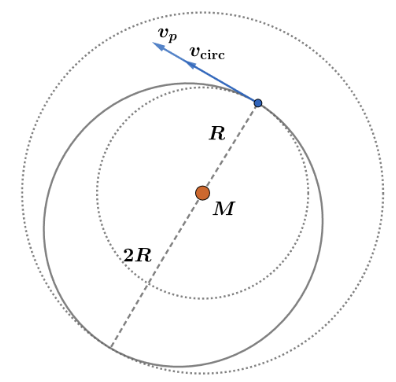

A satellite is initially in a circular orbit of radius \(R\) around a planet of mass \(M\). It fires its rockets to instantaneously increase its speed by \(\Delta v\), keeping the direction of its velocity the same, so that it enters an elliptical orbit whose maximum distance from the planet is \(2R\).

What is the value of \(\Delta v\)? (Hint: when the satellite is in an elliptical orbit with semimajor axis \(a\), its total energy per unit mass is

\[ -\frac{GM}{2a}.\]

(A) \(0.08 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\)

(B) \(0.15 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\)

(C) \(0.22 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\)

(D) \(0.29 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\)

(E) \(0.41 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\)

P18 solution

Recall the velocity for a circular orbit is given by

\[ v_{\text{circ}} = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\]

Recall from the elliptical orbit equations that the velocity at the perigee is given by

\[ v_p = \frac{a+c}{b} \sqrt{\frac{GM}{a}} = \sqrt{\frac{r_a}{r_p}} \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{r_a + r_p}} = \sqrt{\frac{2R}{R}} \sqrt{\frac{2GM}{2R + R}} = \sqrt{\frac{4GM}{3R}}\]

Then

\[ \Delta v = v_p - v_{\text{circ}} = \left( \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}} - 1 \right) \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}} = 0.15 \sqrt{\frac{GM}{R}}\]

So the answer is (B).

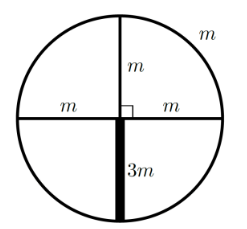

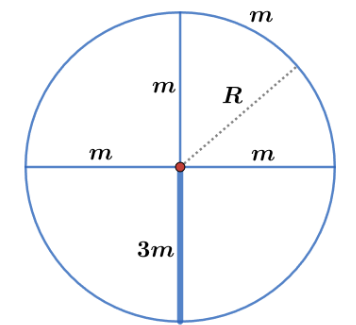

P19

A wheel of radius \(R\) has a thin rim and four spokes, each of which has uniform density.

The entire rim has mass \(m\), three of the spokes each have mass \(m\), and the fourth spoke has mass \(3m\).

The wheel is suspended on a horizontal frictionless axle passing through its center.

If the wheel is slightly rotated from its equilibrium position, what is the angular frequency of small oscillations?

(A) \(\sqrt{\frac{g}{3R}}\)

(B) \(\sqrt{\frac{g}{2R}}\)

(C) \(\sqrt{\frac{2g}{3R}}\)

(D) \(\sqrt{\frac{g}{R}}\)

(E) \(\sqrt{\frac{7g}{6R}}\)

P19 solution

Recall that the angular frequency of a physical pendulum is given by

\[ \omega = \sqrt{\frac{Mgd}{I}}\]

where \(M\) is the total mass, \(d\) is the distance between the center of mass (CM) and the pivot point, and \(I\) is the total moment of inertia. We have

\[ M = m + m + m + m + m + 3m = 7m\]

\[ I = mR^2 + 3 \left(\frac{1}{3} mR^2 \right) + \frac{1}{3} (3m) R^2 = 3mR^2\]

To find the CM, we can think of the wheel as the superposition of a spoke of mass \(2m\) with a symmetric wheel that has four spokes of equal mass \(m\).

The CM of each object is at its center, so we can place all their mass at those points.

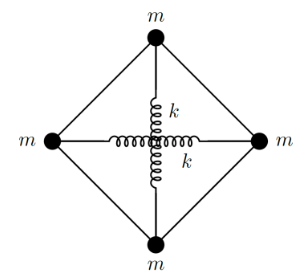

P20

Four massless rigid rods are connected into a quadrilateral by four hinges.

The hinges have mass \(m\) and allow the rods to freely rotate.

A spring of spring constant \(k\) is connected across each of the diagonals,

so that the springs are at their relaxed length when the rods form a square.

Assume the springs do not interfere with each other.

If the square is slightly compressed along one of its diagonals,

its shape will oscillate over time.

What is the period of these oscillations?

(A) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{m}{4k}}\)

(B) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{m}{2k}}\)

(C) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{m}{k}}\)

(D) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{2m}{k}}\)

(E) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{4m}{k}}\)

P20 solution

Suppose we compress along one diagonal by displacing the top and bottom masses each by \(x\)

towards each other. By conservation of rod length, the two masses in the middle move apart,

each displacing by \(x\) also.

We derive the equation of motion for \(x(t)\) by energy conservation.

The kinetic energy of the system is given by:

\($ K = 4 \left(\frac{1}{2} m \dot{x}^2 \right)\)$

since all masses move by the same amount and have the same speed.

The potential energy of the system is given by:

\($ U = 2 \left[ \frac{1}{2} k (2x)^2 \right]\)$

since both springs change length by \(2x\).

We have:

\($ E = K + U = 2m\dot{x}^2 + 4kx^2\)$

Conserving energy,

\($ 0 = \frac{dE}{dt} = 2m(2\dot{x}\ddot{x}) + 4k(2x\dot{x}) = \dot{x} (4m\ddot{x} + 8kx)\)$

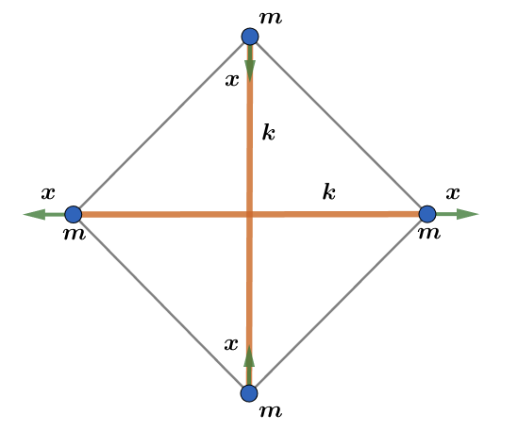

P21

A syringe is filled with water of density \(\rho\) and negligible viscosity.

Its body is a cylinder of cross-sectional area \(A_1\), which gradually tapers

into a needle with cross-sectional area \(A_2 \ll A_1\).

The syringe is held in place, and its end is slowly pushed inward

by a force \(F\), so that it moves with constant speed \(v\).

Water shoots straight out of the needle’s tip.

What is the approximate value of \(F\)?

(A) \(\rho v^2 A_1\)

(B) \(\frac{\rho v^2 A_1^2}{2A_2}\)

(C) \(\frac{\rho v^2 A_1^2}{A_2}\)

(D) \(\frac{\rho v^2 A_1^3}{2A_2^2}\)

(E) \(\frac{\rho v^2 A_1^3}{A_2^2}\)

P21 solution

We conserve energy by Bernoulli’s principle,

\[ P_1 + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_1^2 + \rho g y_1 = P_2 + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2 + \rho g y_2\]

applied to the two ends of the syringe. In our case,

\[ y_1 = y_2\]

\[ P_1 = P_0 + \frac{F}{A_1}\]

\[ P_2 = P_0\]

so we have

\[ P_0 + \frac{F}{A_1} + \frac{1}{2} \rho v^2 = P_0 + \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2\]

\[ F = \frac{A_1}{2} \rho (v_2^2 - v^2)\]

By the continuity equation,

\[ A_1 v = A_2 v_2\]

\[ v_2 = \frac{A_1 v}{A_2}\]

Substituting into our expression for \(F\),

\[ F = \frac{A_1}{2} \rho \left( \frac{A_1^2}{A_2^2} - 1 \right) v^2 \approx \frac{A_1^3 \rho v^2}{2 A_2^2}\]

using the assumption that \(A_1 \gg A_2\). Thus, the answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

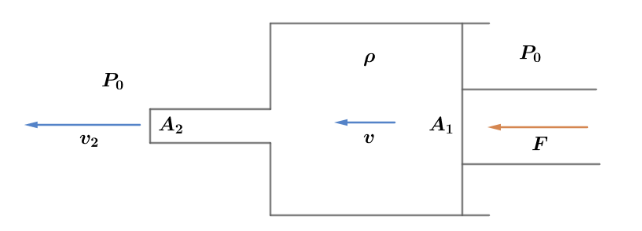

P22

A spherical shell is made from a thin sheet of material with a mass per area of \(\sigma\).

Consider two points, \(P_1\) and \(P_2\), which are close to each other,

but just inside and outside the sphere, respectively.

If the accelerations due to gravity at these points are \(\mathbf{g}_1\) and \(\mathbf{g}_2\), respectively,

what is the value of \(\left| \mathbf{g}_1 - \mathbf{g}_2 \right|\)?

(A) \(\pi G \sigma\)

(B) \(\frac{4\pi G \sigma}{3}\)

(C) \(2\pi G \sigma\)

(D) \(4\pi G \sigma\)

(E) \(8\pi G \sigma\)

P22 solution

By the shell theorem, the gravitational field inside a spherical shell is

\[ g_1 = 0\]

while the gravitational field outside is the same as that of a point located at the center,

\[ g_2 = \frac{GM}{R^2}\]

Thus,

\[ \Delta g = g_2 - g_1 = \frac{GM}{R^2} = \frac{G(4\pi R^2 \sigma)}{R^2} = 4\pi G \sigma\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

P23

Collisions between ping pong balls and paddles are not perfectly elastic.

Suppose that if a player holds a paddle still and drops a ball on top of it from any height \(h\),

it will bounce back up to height \(h/2\).

To keep the ball bouncing steadily, the player moves the paddle up and down,

so that it is moving upward with speed \(1.0 \, \text{m/s}\) whenever the ball hits it.

What is the height to which the ball is bouncing?

(A) \(0.21 \, \text{m}\)

(B) \(0.45 \, \text{m}\)

(C) \(1.0 \, \text{m}\)

(D) \(1.7 \, \text{m}\)

(E) There is not enough information to determine the height.

P23 solution

Since the ball bounces back up to half the initial height \(h\), it loses half its energy \(E\)

after colliding with a stationary paddle. We have \(E \propto v^2\)

so its speed is reduced by a factor of \(\sqrt{2}\).

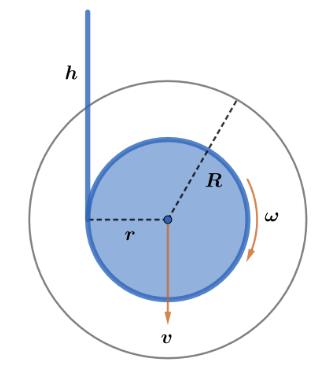

Now we let the paddle move such that it’s moving upward with speed \(v_0\)

when it collides with the ball.

To determine what happens, we can go to the frame of the paddle

where we know the ball’s speed gets reduced by a factor of \(\sqrt{2}\):

P24

When a projectile falls through a fluid, it experiences a drag force

proportional to the product of its cross-sectional area, the fluid density \(\rho_f\),

and the square of its speed. Suppose a sphere of density \(\rho_s \gg \rho_f\)

of radius \(R\) is dropped in the fluid from rest.

When the projectile has reached half of its terminal velocity,

which of the following is its displacement proportional to?

(A) \(R \sqrt{\rho_s / \rho_f}\)

(B) \(R \rho_s / \rho_f\)

(C) \(R (\rho_s / \rho_f)^{3/2}\)

(D) \(R (\rho_s / \rho_f)^2\)

(E) \(R (\rho_s / \rho_f)^3\)

P24 solution

For a particle falling under quadratic drag \(F_d = bv^2\), recall the characteristic time \(\tau\)

determines how long it takes the particle’s speed \(v\) to be on the order of the terminal velocity \(v_t\).

Similarly, the characteristic length \(l\) determines how far the particle has traveled

when its speed \(v \sim v_t\).

These intrinsic parameters can be found by dimensional analysis:

\[ [m] = M\]

\[ [g] = \frac{L}{T^2}\]

\[ [b] = \left[ \frac{F_d}{v^2} \right] = \frac{M L / T^2}{L^2 / T^2} = \frac{M}{L}\]

To make a length, we can divide \(m\) by \(b\) (since \(g\) has dimensions of time, so it can’t appear). Thus,

\[ l = \frac{m}{b}\]

In our case, we are given \(b \propto A \rho_f \propto R^2 \rho_f\)

and we also have \(m \propto R^3 \rho_s\),

\[ l \propto \frac{R^3 \rho_s}{R^2 \rho_f} = \frac{R \rho_s}{\rho_f}\]

The displacement when \(v = v_t / 2\) is proportional to \(l\),

so the answer is B.

P25

- A yo-yo consists of two massive uniform disks of radius \(R\) connected by a thin axle.

A thick string is wrapped many times around the axle, so that the end of the string

is initially a distance \(R\) from the axle.

Then, the end of the string is held in place and the yo-yo is dropped from rest.

Assume that energy losses are negligible, and that the string has negligible mass

and always remains vertical. Below, we show a cross-section of the yo-yo

partway through its descent.

Between the moment the yo-yo is released and the moment the string completely unwinds,

which of the following is true regarding the yo-yo’s acceleration?

- (A) It is always zero.

- (B) It points downward, but decreases in magnitude over time.

- (C) It points downward and has constant magnitude.

- (D) It points downward, but increases in magnitude over time.

- (E) None of the above.

P25 solution

We can find the yo-yo’s velocity \(v\) at any point by conservation of energy. If it has fallen down by height \(h\), then we have

\[ Mgh = \frac{1}{2} M v^2 + \frac{1}{2} I \omega^2\]

Since the yo-yo is made up of two stacked disks,

\[ I = \frac{1}{2} M R^2\]

The yo-yo moves down at the rate at which the string unwinds, so

\[ v = r \omega\]

Substituting these into the first equation,

\[ Mgh = \frac{1}{2} M v^2 + \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{1}{2} M R^2\right) \frac{v^2}{r^2} = \frac{M v^2}{2} \left( 1 + \frac{R^2}{2r^2} \right)\]

Solving for \(v\),

\[ 2gh = v^2 \left( 1 + \frac{R^2}{2r^2} \right)\]