F=ma 2023 solutions

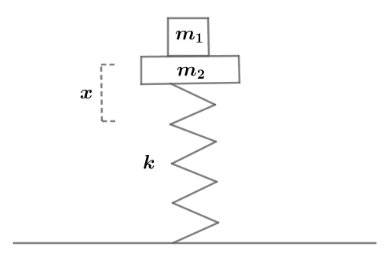

P01

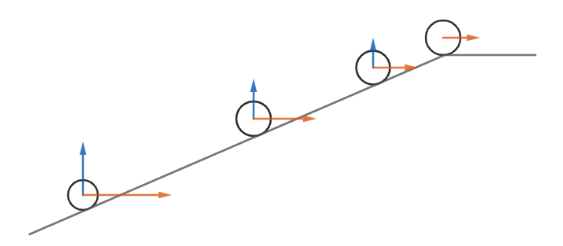

A bead on a circular hoop with radius \(2\,\text{m}\) travels counterclockwise for \(10\,\text{s}\) and completes \(2.25\) rotations, at which point it reaches the position shown.

In the past \(10\,\text{s}\), what were its average speed and the direction of its average velocity?

- (A) \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{5} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}, \nwarrow\)

- (B) \(\frac{2\pi}{5} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}, \nwarrow\)

- (C) \(\frac{9\pi}{10} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}, \nwarrow\)

- (D) \(\frac{2\pi}{5} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}, \searrow\)

- (E) \(\frac{9\pi}{10} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}, \searrow\)

P01 solution

The average speed is given by

\[ \bar{v} = \frac{d}{\Delta t} = \frac{R \Delta \theta}{\Delta t} = \frac{(2 \text{ m})(2.25 \cdot 2\pi)}{10 \text{ s}} = \frac{9\pi}{10} \text{ m/s}\]

The average velocity is given by

\[ \vec{v}_{\text{ave}} = \frac{\Delta \vec{r}}{\Delta t}\]

so it points in the same direction as the displacement \(\Delta \vec{r}\). Thus, the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

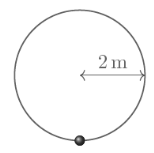

P02

A mass on an ideal pendulum is released from rest at point I. When it reaches point II, which of the following shows the direction of its acceleration?

P02 solution

The pendulum has a nonzero speed, so it has a centripetal acceleration \(\vec{a}_c\) directed towards the center of rotation. The pendulum also has a tangential acceleration \(\vec{a}_t\) due to gravity. The total acceleration \(\vec{a}\) is given by the vector sum:

\[ \vec{a} = \vec{a}_c + \vec{a}_t\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

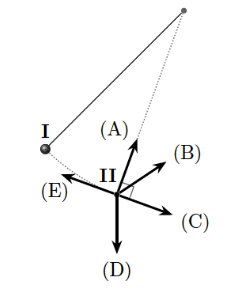

P03

A soccer ball is kicked up a hill with a flat top, as shown. The ball bounces twice on the hill at the points shown, then lands on the top and begins rolling horizontally.

Which of the following graphs represents the vertical component of its velocity \(v_y\) as a function of time \(t\)?

P03 solution

Since the vertical distance between the ball’s collision point and subsequent peak height is decreasing, the vertical velocity \(v_y\) gets smaller at each collision. Between the collisions, the vertical velocity decreases linearly due to gravity,

\[ v_y(t) = v_{y0} - g t\]

At the end, we have \(v_y = 0\). Thus, the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

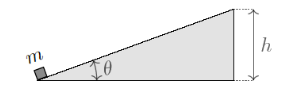

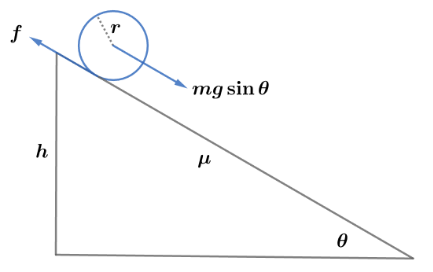

P04

A box of mass \(m\) is at the bottom of an inclined plane with angle \(\theta\) to the horizontal, and height \(h\).

A person drags the box very slowly up the plane by applying a force parallel to the plane. The coefficient of kinetic friction between the box and the plane is \(\mu_k\).

When the box reaches the top of the plane, how much work has the person done?

P04 solution

The force \(F\) the person applies has to balance the component of gravity parallel to the inclined plane and kinetic friction,

\[ F = mg \sin\theta + \mu_k N = mg (\sin\theta + \mu_k \cos\theta)\]

The distance \(d\) the box is dragged up is

\[ d = \frac{h}{\sin\theta}\]

The work done is then given by

\[ W = F d = mgh (1 + \mu_k \cot\theta)\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

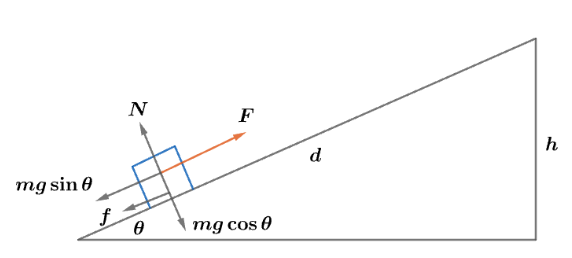

P05

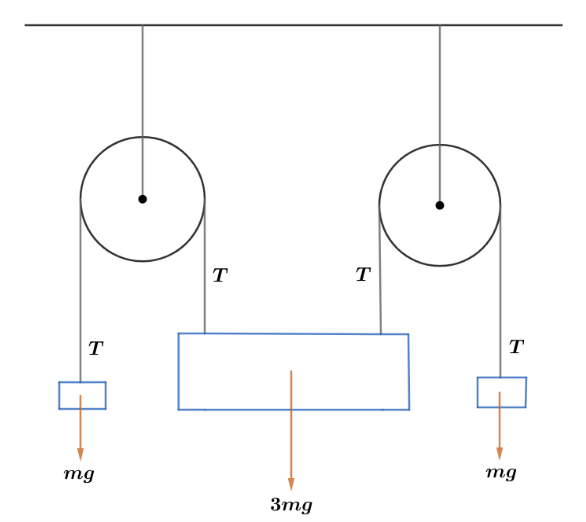

Two blocks of mass \(m\) and a block of mass \(3m\) are attached to a system of massless fixed pulleys and massless string, as shown.

Assume all surfaces are frictionless. What is the acceleration of each mass \(m\)?

P05 solution

Applying Newton’s 2nd law to the blocks and using the fact that they move together with the same acceleration (middle block down and side blocks up), we have

\[ T - mg = ma\]

\[ 3mg - 2T = 3ma\]

\[ T - mg = ma\]

Adding these equations together yields

\[ mg = 5ma\]

\[ a = \frac{g}{5}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

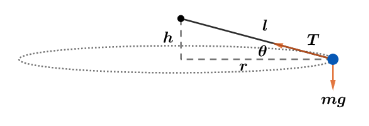

P06

A ball at the end of a rope of length \(0.5 \text{ m}\) is swung in a horizontal circle, with a speed of \(15 \text{ m/s}\). The other end of the rope is fixed in place. What is the height difference between the ends of the rope?

P06 solution

We have

\[ \sin\theta = \frac{h}{l}\]

where \(h\) is the height difference between the ends of the rope.

Considering the force vectors, we have

\[ \tan\theta = \frac{mg}{mv^2 / r} = \frac{g r}{v^2}\]

Since \(h \ll l\), we can make the small angle approximation \(\tan\theta \approx \sin\theta\),

\[ \frac{g r}{v^2} = \frac{h}{l}\]

Furthermore, \(\cos\theta \approx 1\) so \(r = l \cos\theta \approx l\). Substituting this in the previous equation,

\[ \frac{g l}{v^2} = \frac{h}{l}\]

\[ h = \frac{g l^2}{v^2} = \frac{(10 \text{ m/s}^2)(0.5 \text{ m})^2}{(15 \text{ m/s})^2} = 1.1 \text{ cm}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{A}\).

P07

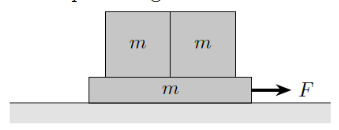

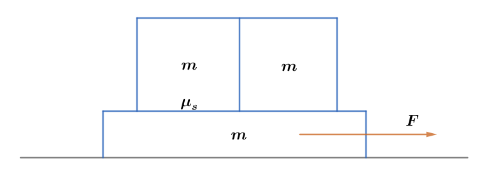

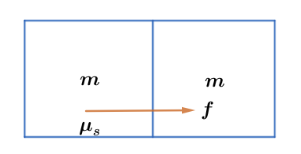

Two boxes are stacked side-by-side on top of a larger box, as shown.

All three boxes have mass \(m\), the coefficient of static friction between the left box and the bottom box is \(\mu_s\), and all other surfaces are frictionless. A rightward force \(F\) is applied to the bottom box. What is the minimum value of \(\mu_s\) so that the upper boxes don’t slide?

- (A) \(\frac{2F}{mg}\)

- (B) \(\frac{3F}{mg}\)

- (C) \(\frac{F}{2mg}\)

- (D) \(\frac{2F}{3mg}\)

- (E) \(\frac{F}{3mg}\)

P07 solution

If the upper boxes don’t slide, then all three boxes move together. Applying Newton’s 2nd law to the combined system of boxes, we have

\[ F = 3m a\]

\[ a = \frac{F}{3m}\]

Applying Newton’s 2nd law to the upper two boxes, we have

\[ f = 2ma\]

We know the maximum value of static friction \(f \leq \mu_s N = \mu_s mg\), so

\[ 2ma \leq \mu_s mg\]

\[ \mu_s \geq \frac{2a}{g} = \frac{2F}{3mg}\]

Thus, the answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

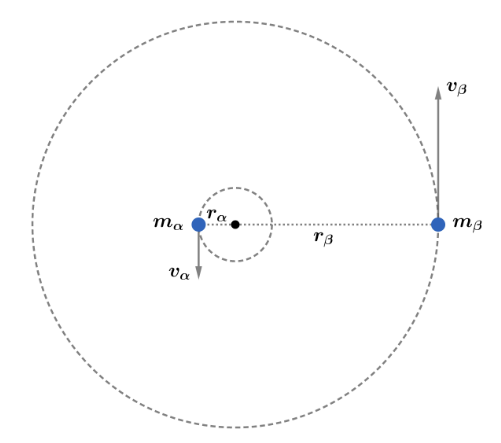

P08

Two stars \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), with masses satisfying \(\frac{m_{\alpha}}{m_{\beta}} = 10\), are in circular orbits around each other. In the rest frame of this system, find the ratio of the speeds \(\frac{v_{\alpha}}{v_{\beta}}\).

- (A) \(\frac{1}{11}\)

- (B) \(\frac{1}{10}\)

- (C) \(\frac{1}{9}\)

- (D) \(9\)

- (E) \(10\)

P08 solution

The force of gravity provides the centripetal acceleration, so we have

\[ F_g = \frac{m_{\alpha} v_{\alpha}^2}{r_{\alpha}} = \frac{m_{\beta} v_{\beta}^2}{r_{\beta}}\]

\[ \frac{v_{\alpha}}{v_{\beta}} = \sqrt{\frac{m_{\beta} r_{\alpha}}{m_{\alpha} r_{\beta}}}\]

Since we are in the CM frame, \(m_{\alpha} r_{\alpha} = m_{\beta} r_{\beta}\), so

\[ \frac{v_{\alpha}}{v_{\beta}} = \frac{m_{\beta}}{m_{\alpha}} = \frac{1}{10}\]

We could have also gotten this by noting that the total momentum is zero in the CM frame, so \(m_{\alpha} v_{\alpha} = m_{\beta} v_{\beta}\). Thus, the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

P09

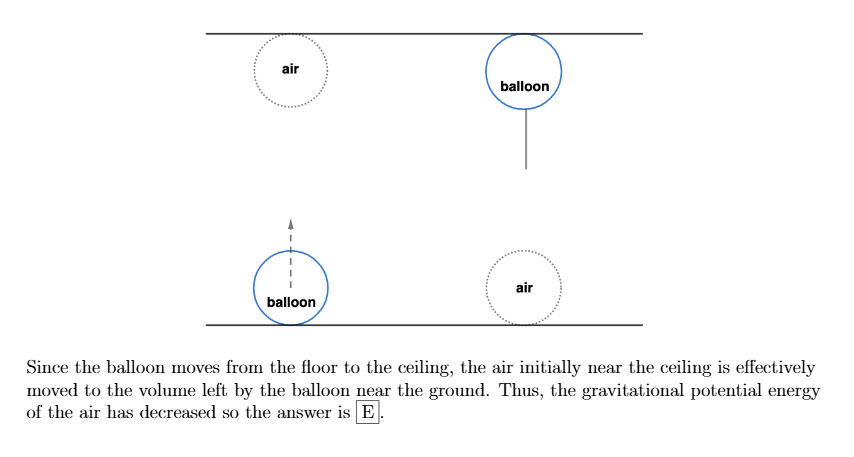

A helium balloon is released from the floor in a room at rest, then slowly rises and comes to rest touching the ceiling. During this process, the gravitational potential energy of the balloon has increased. Since energy is conserved, the energy of something else must have decreased during this process. Which of the following is the main contribution to this decrease?

- (A) The kinetic energy of the balloon decreased.

- (B) The elastic potential energy of the balloon decreased.

- (C) The thermal energy of the air in the balloon decreased.

- (D) The thermal energy of the air in the room decreased.

- (E) The gravitational potential energy of the air in the room decreased.

P09 solution

Since the balloon moves from the floor to the ceiling, the air initially near the ceiling is effectively moved to the volume left by the balloon near the ground. Thus, the gravitational potential energy of the air has decreased, so the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

P10

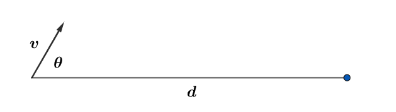

An archer takes aim at a target that is 100 m away. Assuming she holds the bow at the same height as the center of the target and shoots an arrow with velocity \(v = 100\) m/s, at what angle above the horizontal should she aim the bow so that the arrow hits the center of the target?

- (A) \(\frac{\arccos(1/5)}{2}\)

- (B) \(\frac{\arcsin(1/5)}{2}\)

- (C) \(\frac{\arccos(1/10)}{2}\)

- (D) \(\frac{\arcsin(1/10)}{2}\)

- (E) \(\frac{\arctan(2/5)}{2}\)

P10 solution

Recall the range equation from kinematics,

\[ d = \frac{v^2 \sin(2\theta)}{g}\]

In our case,

\[ \theta = \frac{1}{2} \arcsin \left( \frac{g d}{v^2} \right) = \frac{1}{2} \arcsin \left( \frac{(10 \text{ m/s}^2)(100 \text{ m})}{(1000 \text{ m/s})^2} \right) = \frac{1}{2} \arcsin \left( \frac{1}{10} \right)\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

P11

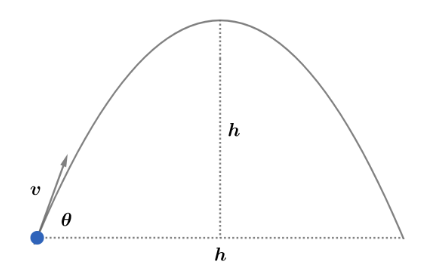

A projectile is thrown from a horizontal surface and reaches a maximum height \(h\)

while also landing at a distance \(h\) from the launch point.

Neglecting air resistance, what is the maximum height for a projectile thrown directly upward with the same initial speed?

- (A) \(\frac{17h}{16}\)

- (B) \(\frac{13h}{12}\)

- (C) \(\frac{9h}{8}\)

- (D) \(\frac{5h}{4}\)

- (E) \(2h\)

P11 solution

Recall the range and height equations,

\[ R = \frac{v^2 \sin(2\theta)}{g}\]

\[ H = \frac{v^2 \sin^2 \theta}{2g}\]

Since \(R = H\),

\[ \frac{v^2 \sin(2\theta)}{g} = \frac{v^2 \sin^2 \theta}{2g}\]

\[ 2 \sin\theta \cos\theta = \frac{\sin^2 \theta}{2}\]

\[ \tan \theta = 4\]

Because we reach height \(h\),

\[ h = \frac{v^2 \sin^2 \theta}{2g} = \frac{v^2 \sin^2 (\arctan 4)}{2g} = \frac{8 v^2}{17g}\]

\[ v^2 = \frac{17gh}{8}\]

If we launch with this speed upwards, then by energy conservation,

\[ \frac{1}{2} m v^2 = mgh'\]

\[ h' = \frac{v^2}{2g} = \frac{17h}{16}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{A}\).

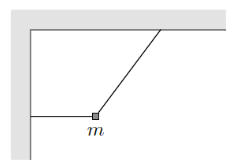

P12

A block of mass \(m\) is initially held in place by two massless strings, as shown.

The tension in the diagonal string is \(T_1\). Next, the horizontal string is cut, and immediately afterward, the tension in the diagonal string is \(T_2\).

Which of the following is true?

- (A) \(T_1 < mg < T_2\)

- (B) \(T_2 < mg < T_1\)

- (C) \(T_1 < T_2 < mg\)

- (D) \(mg < T_2 < T_1\)

- (E) \(T_1 = T_2 < mg\)

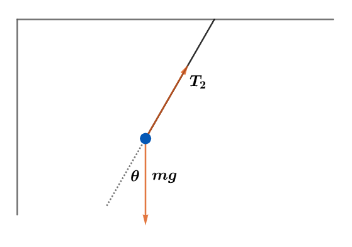

P12 solution

Initially, we balance forces to obtain

\[ T_1 = \sqrt{(mg)^2 + T_0^2} > mg\]

After the horizontal string is cut, the tension in the diagonal string balances the radial component of gravity,

\[ T_2 = mg \cos\theta < mg\]

Thus, we have \(T_2 < mg < T_1\), so the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

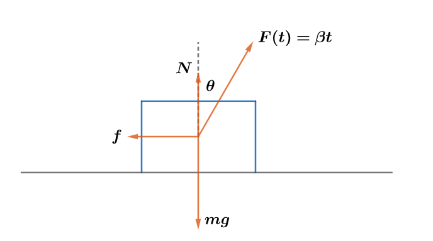

P13

A uniform box with mass \(m\) is at rest on a horizontal surface, and the coefficient of static friction between them is \(\mu_s\).

A force directed at an angle of \(85^\circ\) above the horizontal is applied to the center of the box, with a linearly increasing magnitude \(F = \beta t\).

The box will eventually slide or lift off the ground. Which of the following is correct?

- (A) If \(\mu_s < \tan 85^\circ\), the box will lift off the ground first.

- (B) If \(\mu_s < \tan 85^\circ\), the box will slide first.

- (C) For any value of \(\mu_s\), the box will lift off the ground first.

- (D) For any value of \(\mu_s\), the box will slide first.

- (E) The answer depends on the values of \(\beta\), \(g\), and \(m\).

P13 solution

Lift-off occurs when the vertical component of the external force balances the weight,

\[ F(t) \cos\theta = mg\]

\[ \beta t \cos\theta = mg\]

\[ t_l = \frac{mg}{\beta \cos\theta}\]

Sliding occurs when the horizontal component of the external force overcomes static friction,

\[ F(t) \sin\theta = \mu_s N = \mu_s (mg - F(t) \cos\theta)\]

\[ \beta t \sin\theta = \mu_s mg - \mu_s \beta t \cos\theta\]

\[ \beta t (\sin\theta + \mu_s \cos\theta) = \mu_s mg\]

\[ t_s = \frac{\mu_s mg}{\beta (\sin\theta + \mu_s \cos\theta)} = \frac{\mu_s \cos\theta}{\sin\theta + \mu_s \cos\theta} t_l\]

Since the prefactor is less than one, \(t_s < t_l\), so the block will slide first. The answer is \(\boxed{D}\).

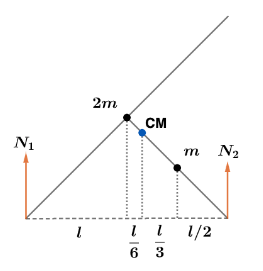

P14

The object shown below is made of three rigidly connected, identical rods with uniform density.

When it stands upright on a horizontal table, what fraction of its weight rests on the left leg?

- (A) \(\frac{1}{12}\)

- (B) \(\frac{1}{6}\)

- (C) \(\frac{1}{4}\)

- (D) \(\frac{1}{3}\)

- (E) \(\frac{5}{12}\)

P14 solution

We first find the horizontal location of the CM for this object. We can replace the two rods connected in a line with a point mass \(2m\) at their center. We can replace the third rod with a point mass \(m\) located at its center.

Let \(l\) be the length of the horizontal projection of a rod. Then the horizontal distance between \(2m\) and \(m\) is \(l/2\). The CM is a third of the way from \(2m\) to \(m\), so

\[ x_{CM} = \frac{1}{3} \left(\frac{l}{2}\right) = \frac{l}{6}\]

to the right of \(2m\).

Choosing the CM as the axis of rotation, we can balance torques from the normal forces,

\[ N_1 \left(\frac{7l}{6}\right) = N_2 \left(\frac{5l}{6}\right)\]

\[ \frac{N_2}{N_1} = \frac{7}{5}\]

The fraction of the weight on the left leg is given by

\[ f = \frac{N_1}{W} = \frac{N_1}{N_1 + N_2} = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{7}{5}} = \frac{5}{12}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

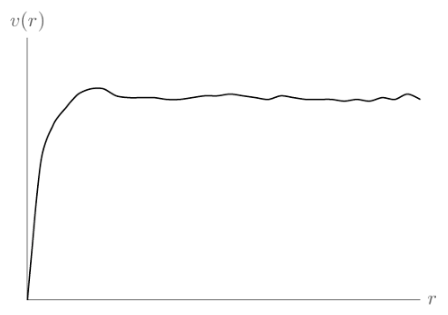

P15

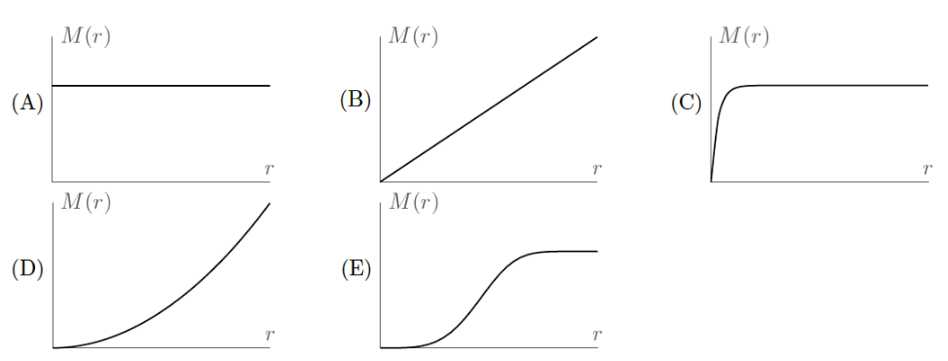

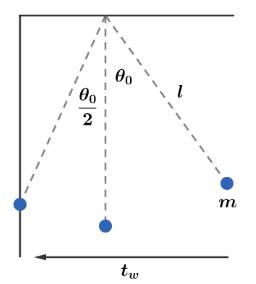

The following plot shows the speed \(v(r)\) at which stars orbit about the center of a galaxy, as a function of their distance \(r\) from the center.

Assuming the galaxy has a spherically symmetric mass distribution, which plot best shows the mass of the galaxy \(M(r)\) enclosed within radius \(r\)?

P15 solution

By Gauss’s law for gravity, we have

\[ \Phi_g = -4\pi GM_{\text{enc}}\]

The flux \(\Phi_g \propto g(r) \cdot r^2\) where \(g(r)\) is the gravitational field at radius \(r\), so

\[ g(r) r^2 \propto M(r)\]

\[ g(r) \propto \frac{M(r)}{r^2}\]

where \(M(r)\) is the mass enclosed in a sphere of radius \(r\). The gravitational force provides the centripetal acceleration, so we have

\[ mg(r) = \frac{m v(r)^2}{r}\]

\[ v(r)^2 = r g(r) \propto \frac{M(r)}{r}\]

Thus,

\[ M(r) \propto r v(r)^2\]

Since \(v(r) \sim\) const from the plot, \(M(r) \propto r\), so mass enclosed increases linearly with the radius. The answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

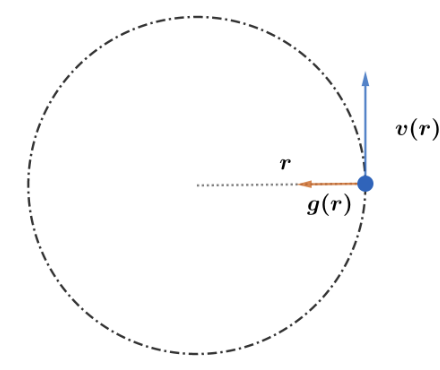

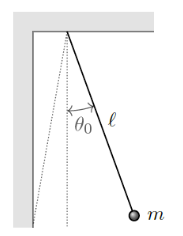

P16

A bead attached to a string of length \(\ell = 10\) m is released from a very small angle \(\theta_0\) to the vertical.

A wall is placed in the path of the bead, such that the bead collides elastically with the wall

when the string is at an angle \(\theta_0/2\) to the vertical, as shown.

What is the time interval between the bead’s collisions with the wall?

- (A) \(\frac{2\pi}{3}\) s

- (B) \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) s

- (C) \(\frac{4\pi}{3}\) s

- (D) \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) s

- (E) \(2\pi\) s

P16 solution

The bead is in simple harmonic motion since it is a simple pendulum undergoing small oscillations. Thus, we have

\[ \theta(t) = \theta_0 \cos(\omega t)\]

where

\[ \omega = \sqrt{\frac{g}{l}}\]

is the angular frequency of a simple pendulum. Note \(\theta(t = 0) = \theta_0\) as required. Then the time \(t_w\) it takes to reach the wall from the start is given by

\[ -\frac{\theta_0}{2} = \theta_0 \cos(\omega t_w)\]

\[ \cos(\omega t_w) = -\frac{1}{2}\]

\[ \omega t_w = \frac{2\pi}{3}\]

\[ t_w = \frac{2\pi}{3} \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}}\]

This is half the time between wall collisions, so

\[ t_c = 2t_w = \frac{4\pi}{3} \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}} = \frac{4\pi}{3} \sqrt{\frac{10 \text{ m}}{10 \text{ m/s}^2}} = \frac{4\pi}{3} \text{ s}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{C}\).

P17

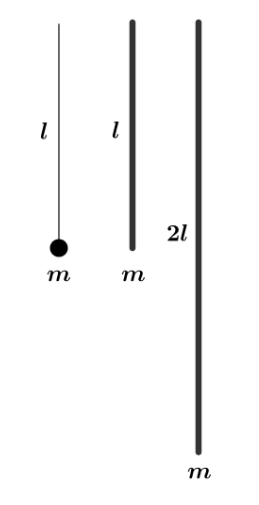

Three physical pendulums are built as shown.

-

The first is a typical pendulum with a massless rope.

-

The second and third are made of uniform rods.

What is the correct ranking of the moments of inertia \(I_1, I_2,\) and \(I_3\) about the pivot points? -

(A) \(I_1 > I_2 > I_3\)

-

(B) \(I_3 > I_2 > I_1\)

-

(C) \(I_1 = I_3 > I_2\)

-

(D) \(I_2 > I_3 > I_1\)

-

(E) \(I_3 > I_1 > I_2\)

P17 solution

Recall the moments of inertia,

\[ I_{\text{point}} = m r^2\]

and

\[ I_{\text{rod, end}} = \frac{1}{3} m l^2\]

In our case,

\[ I_1 = m l^2\]

\[ I_2 = \frac{1}{3} m l^2\]

\[ I_3 = \frac{1}{3} m (2l)^2 = \frac{4}{3} m l^2\]

Thus, \(I_3 > I_1 > I_2\), so the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

P18

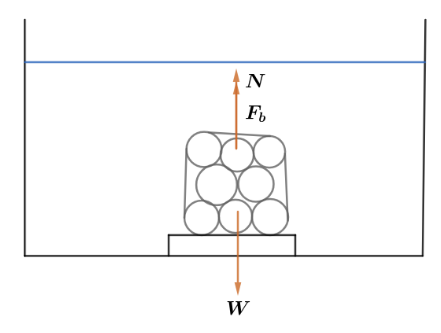

Alice, Bob, and Carol are each given identical airtight bags containing identical rocks, and a large tub of water with a scale sitting on the bottom. Each of them measures the weight of their bag and rock by putting the bag on the scale, using three slightly different procedures.

- Alice closes the bag carefully, so that there is no air inside.

- Bob fills the rest of the bag with water before closing it.

- Carol closes the bag loosely, so that it contains some air.

What is the correct ranking of their measured weights \(W_A, W_B, W_C\)?

(A) \(W_C < W_A < W_B\)

(B) \(W_A < W_C < W_B\)

(C) \(W_A < W_C = W_B\)

(D) \(W_A = W_C < W_B\)

(E) \(W_C < W_A = W_B\)

P18 solution

Balancing forces, we have

\[ N = W - F_b\]

where \(N\) is the normal force (measured by the scale), \(W\) is the weight of everything inside the bag, and \(F_b\) is the buoyant force on the bag. We have

\[ N_{\text{Alice}} = W_{\text{rocks}} - F_{b, \text{rocks}}\]

\[ N_{\text{Bob}} = W_{\text{rocks}} + W_{\text{water}} - F_{b, \text{rocks}} - F_{b, \text{water}} = N_{\text{Alice}}\]

using the fact that \(W_{\text{water}} = F_{b, \text{water}}\) by Archimedes’ principle.

\[ N_{\text{Carol}} = W_{\text{rocks}} + W_{\text{air}} - F_{b, \text{rocks}} - F_{b, \text{air}} < N_{\text{Alice}}\]

since \(W_{\text{air}} < F_{b, \text{air}}\) as the density of air is less than the density of water. Thus,

\[ W_C < W_A = W_B\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{E}\).

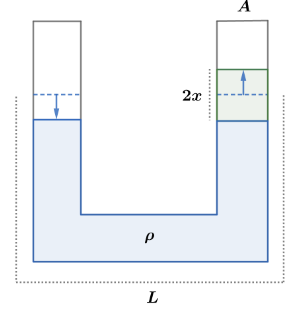

P19

A U-tube manometer consists of a uniform diameter cylindrical tube that is bent into a U shape. It is originally filled with water that has a density \(\rho_w\). The total length of the column of water is \(L\). Ignore surface tension and viscosity.

- The water is displaced slightly so that one side moves up a distance \(x\) and the other side lowers a distance \(x\). Find the frequency of oscillation.

(A) \(\frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{2g}{L}}\)

(B) \(2\pi \sqrt{\frac{g}{L}}\)

(C) \(\frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{2L}{g}}\)

(D) \(\frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{g}{\rho_w}}\)

(E) \(2\pi \sqrt{\rho_w g L}\)

P19 solution

Suppose we displace the water so that the right side moves up by distance \(x\) and the left side moves down by distance \(x\). Then the extra weight on the right side is

\[ F = \rho V_{\text{extra}} g = \rho A (2x) g\]

where \(A\) is the cross-sectional area of the U-tube. This force accelerates all the water, so by Newton’s 2nd law,

\[ ma = -F = -2 \rho A x g\]

where the minus sign accounts for the fact that the force is restoring. Since \(m = \rho V = \rho A L\), we have

\[ \rho A L a = -2 \rho A x g\]

\[ a = \ddot{x} = -\frac{2g}{L} x\]

This is of simple harmonic form (\(\ddot{z} = -\omega^2 z\)), so we can identify the angular frequency as

\[ \omega = \sqrt{\frac{2g}{L}}\]

Thus, the frequency is given by

\[ f = \frac{\omega}{2\pi} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{2g}{L}}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{A}\).

P20

Oil with a density half that of water is added to one side of the tube until the total length of oil is equal to the total length of water. Determine the equilibrium height difference between the two sides.

(A) \(L\)

(B) \(L/2\)

(C) \(L/3\)

(D) \(3L/4\)

(E) \(L/4\)

P20 solution

We compute the pressure at the bottom of the U-tube in two ways: through the left side and through the right side. From the left side,

\[ P_{\text{bot}} = P_0 + \rho_{\text{oil}} g L + \rho_{\text{water}} g d\]

From the right side,

\[ P_{\text{bot}} = P_0 + \rho_{\text{water}} g (L - d)\]

Since these are equal, we have

\[ \rho_{\text{oil}} g L + \rho_{\text{water}} g d = \rho_{\text{water}} g (L - d)\]

\[ \rho_{\text{oil}} L = \rho_{\text{water}} (L - 2d)\]

We are given \(\rho_{\text{oil}} = \rho_{\text{water}} / 2\), so

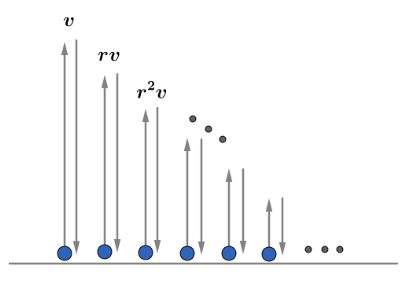

P21

An object launched vertically upward from the ground with a speed of \(50\) m/s bounces off of the ground on the return trip with a coefficient of restitution given by \(C_R = 0.9\), meaning that immediately after a bounce the upward speed is \(90\%\) of the previous downward speed. The ball continues to bounce like this; what is the total amount of time between when the ball is launched and when it finally comes to a rest? Assume the collision time is zero; the bounce is instantaneous. Treat the problem as ideally classical and ignore any quantum effects that might happen for very small bounces.

(A) \(71\) s

(B) \(100\) s

(C) \(141\) s

(D) \(1000\) s

(E) \(\infty\) (the ball never comes to a rest)

P21 solution

If we launch a ball upward with velocity \(v\), then it takes time

\[ v - g t = 0\]

\[ t = \frac{v}{g}\]

to reach the top. Coming down takes the same amount of time, so the time for the first bounce is

\[ T_1 = 2t = \frac{2v}{g}\]

Letting the coefficient of restitution be \(r\), the starting speed for the second bounce is \(rv\). Then the time taken is

\[ T_2 = \frac{2rv}{g}\]

For each subsequent bounce, the speed (and hence time) is reduced by a factor of \(r\). The total time is thus

\[ T_{\text{tot}} = \sum_{i=1}^{\infty} T_i = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{2r^n v}{g} = \frac{2v}{g} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} r^n = \frac{2v}{g} \frac{1}{1 - r}\]

where we used the formula for the sum of an infinite geometric series. Since \(v = 50\) m/s and \(r = 0.9\),

\[ T_{\text{tot}} = \frac{2(50 \text{ m/s}^2)}{(10 \text{ m/s}^2)} \frac{1}{1 - 0.9} = 100 \text{ s}\]

so the answer is \(\boxed{B}\).

P22

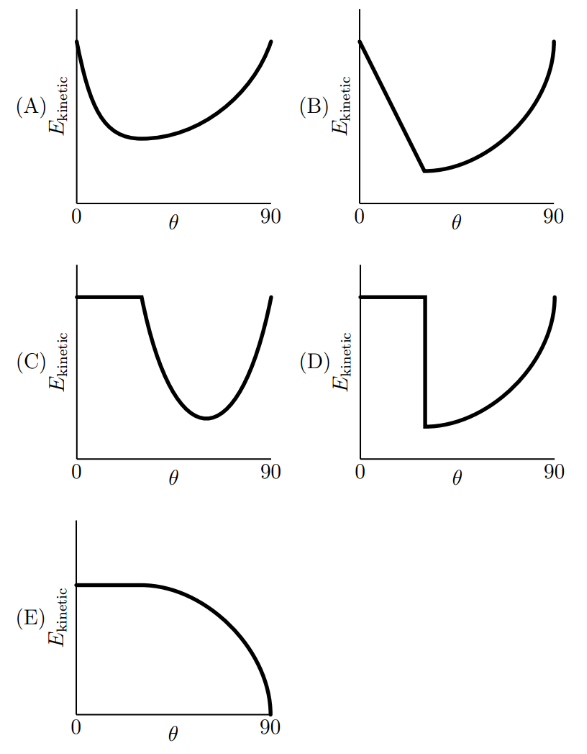

A solid ball is released from rest down inclines of various inclination angles \(\theta\) but through a fixed vertical height \(h\). The coefficient of static and kinetic friction are both equal to \(\mu\). Which of the following graphs best represents the total kinetic energy of the ball at the bottom of the incline as a function of the angle of the incline?

P22 solution

Recall the acceleration of an object rolling without slipping down an incline is given by

\[ a = \frac{g \sin\theta}{1 + \beta}\]

where the object has moment of inertia \(I = \beta m r^2\). For small enough \(\theta\), static friction is large enough to provide sufficient torque since

\[ \tau = f r = I \alpha = \beta m r^2 \alpha\]

Using \(a = r\alpha\) as the object is rolling without slipping,

\[ f = \beta m a = \frac{\beta m g \sin\theta}{1 + \beta}\]

so we see that the required friction force \(f \to 0\) as \(\theta \to 0\). Thus, the object rolls without slipping (no energy loss) for some range of angles \(0 < \theta < \theta_c\).

On the other end, if \(\theta = 90^\circ\) then the object drops vertically and there is also no dissipation. In between when \(\theta_c < \theta < 90^\circ\), the object is rolling with slipping so there is energy dissipation. Going a bit past \(\theta_c\) leads to a small amount of slipping (and energy loss) since the friction force changes continuously. Hence, the only graph that accounts for all these features is \(\boxed{C}\).

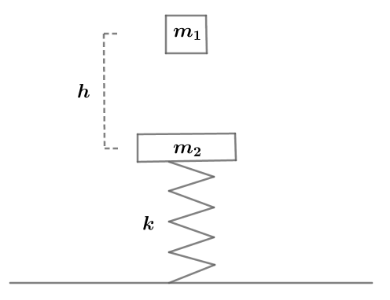

P23

A \(2.0\) kg object falls from rest a distance of \(5.0\) meters onto a \(6.0\) kg object that is supported by a vertical massless spring with spring constant \(k = 72\) N/m. The two objects stick together after the collision, which results in the mass/spring system oscillating. What is the maximum magnitude of the displacement of the \(6.0\) kg object from its original location before it is struck by the falling object?

(A) \(0.27\) m

(B) \(1.1\) m

(C) \(2.5\) m

(D) \(2.8\) m

(E) \(3.1\) m

P23 solution

Conserving energy for \(m_1\), we have

\[ m_1 g h = \frac{1}{2} m_1 v_1^2\]

so \(m_1\) hits \(m_2\) with velocity \(v_1 = \sqrt{2 g h}\). Conserving momentum for the perfectly inelastic collision,

\[ m_1 v_1 = (m_1 + m_2) v\]

so both masses move with velocity

\[ v = \frac{m_1 v_1}{m_1 + m_2} = \frac{m_1 \sqrt{2 g h}}{m_1 + m_2}\]

after the collision.